If you are interested in learning computational chemistry, you cannot ignore the Hartree-Fock theory. Although researchers rarely use the Hartree Fock method directly in their studies nowadays, it is the cornerstone for almost all electronic structure methods. The Hartree Fock method is the practical approach to solving quantum mechanics problems, and when it comes to describing the electronic structure of atoms and molecules, there is no substitute for quantum mechanics. However, comprehending the Hartree Fock theory is a tough challenge, and its difficulty convinces many novice computational chemists to skip it. If truth be told, I had been doing so for some time, but then I realised that the theory would haunt me whenever I tried to learn a new topic in computational chemistry.

Mastering the Hartree Fock method needs a solid understanding of linear algebra and a lot of intellectual effort. However, in this article, I tried to present a straightforward yet insightful explanation of the Hartree Fock theory, which can be used as a starting point for mastering computational methods.

Follow me on LinkedIn

How to read this article

If you know nothing of the Hartree Fock method and just want a quick definition, you can only read the next section. But, if you are a computational researcher who wants a solid understanding of the Hartree Fock theory and how computers solve electronic structure problems, read the entire essay sequentially. The last section describes how the Hartree Fock method works, but you’ll need to know a few concepts from the former passages to grasp that section. Moreover, a moderate understanding of quantum mechanics is required.

Table of Contents

What is the Hartree Fock method?

In a nutshell, the Hartree Fock method is an approximate, iterative computational method for solving the time-independent Schrodinger equation of many-body electronic systems.

A proper description of atomic systems is only possible by applying quantum mechanics rules and solving the legendary Schrodinger equation, which explains the motion of atomic and subatomic particles. But as we know from quantum mechanics textbooks, the Schrodinger equation is only solvable for a few elementary single-electron, hydrogen-like systems exactly. Accordingly, we need approximate methods for more complex systems. There are two fundamental theories to approximate the electronic structure of multi-electron systems in quantum chemistry: the valence bond theory and molecular orbital theory, which is equivalent to the Hartree-Fock theory. The Hartree Fock method is easier to code for computers and hence is the dominant approximate method for solving the time-independent Schrodinger equation.

The Hartree Fock approximation breaks down a multi-electron wave function into a set of one-electron wave functions, called molecular orbitals—indeed, the prevalent concept of molecular orbitals, which is in the mind of every chemist, originates from the Hartree Fock theory. We also call the Hartree Fock method the self-consistent field method because of its particular iterative way of finding the Schrodinger equation solution, which I will explain in the next section.

As I will explain later, the Hartree Fock method itself has insufficient accuracy because it does not account for electron correlation. As a result, researchers rarely use it directly these days. But the Hartree Fock model is the foundation theory behind most of the popular electronic structure methods. Indeed, we have many accurate computational methods that start with the Hartree Fock equation and then fix its electron correlation somehow. They are referred to as post-Hartree Fock methods. Moreover, all the semi-empirical methods and the Kohn–Sham implementation of the Density-functional theory are based on the Hartree-Fock method. Figure 1 shows the relation between Hartree Fock and other electronic structure methods.

The many-body electronic problem

As I mentioned before, the fundamental problem in theoretical chemistry is to solve the Schrodinger equation for a many-body electronic system comprising nuclei and electrons. This section will briefly describe the problem and then explain the brilliant Hartree and Fock’s solution.

Let’s start with the general form of the non-relativistic time-independent Schrodinger equation.

To solve this equation for any system, we must know the system’s Hamiltonian and wave function. According to quantum mechanics, the Hamiltonian operator for a many-body system composed of several nuclei and electrons is:

The above equation is in atomic units for simplicity. Its terms represent the kinetic energy of electrons, the kinetic energy of nuclei, the coulomb attraction between electrons and nuclei, repulsion between electrons and repulsion between nuclei, respectively. You can find the derivation of this equation in quantum chemistry textbooks. Nevertheless, the Born-Oppenheimer approximation states that, since nuclei are much heavier than electrons and move a lot slower, we can consider the electrons moving in the field of fixed nuclei. As a result, we can equate the second term in the above equation with zero and consider the last term as a constant, which can be neglected because adding any constant to an operator does not affect the operator eigenfunctions and only adds to operator eigenvalues. The remaining terms are known as the electronic Hamiltonians, and they represent the motion of N electrons in the field of M fixed nuclei.

If we solve the Schrodinger equation for electronic Hamiltonian, the solution includes the electronic energy and the electronic wave function, which describes the motion of the electrons.

The electronic wave function depends explicitly on the electronic coordinates but parametrically on the nuclear coordinates, so, although the electronic wave function does not include the nuclear coordinates, Ψelec is a different function for different arrangements of the nuclei. The total energy for fixed nuclei also comprises the constant nuclear repulsion.

If we can solve the electronic Shrodinger equation, we can describe the motion of the nuclei by introducing a nuclear Hamiltonian under the same assumptions used to derive the electronic equation. So the major problem in computational chemistry is to solve the electronic Shrodinger equation, which is the goal of the Hartree-Fock method.

To solve the electronic Schrodinger equation, we have no choice but to break down the N electron equation into a set of one-electron equations, namely.

To do so, The electronic Hamiltonian (equation 3) must be separable into a set of one-electron ones.

The first term in this equation is the sum of single-electron kinetic energies. The second is the sum of attractions between each electron and all nuclei. Therefore, the two first terms are separable—note that the separation is based on electrons. But, the last term is the sum of repulsion between all electron-pairs and is not divisible into single electron terms. Hartree suggested we can approximate the electron-electron repulsion averagely. This means, instead of calculating the repulsion for all electron pairs, we can calculate the repulsion between each electron and an average field of all other electrons. By doing so, we can separate the third term into a set of one-electron terms and write the Hamiltonian as a sum of one-electron operators:

vHF is the average potential that the i-th electron experiences because of the other electrons, and f(x) is a one-electron operator called the Fock operator. Using the Fock operator, we can break down the electronic Schrodinger equation into a set of one-electron equations.

Although this equation is a one-electron problem, the Hartree-Fock potential (vHF) depends on the entire system’s wave function. Therefore, this is a nonlinear problem and must be solved iteratively. The Hartree Fock method’s basic idea is that, using an initial trial wave function, the average field is calculated, then the eigenvalue equation (equation 9) is solved using this average field, and a new wave function is produced. The new wave function is used to calculate a new average field, and this procedure is repeated until some convergence criteria are satisfied. The self-consistent-field (SCF) is another name for the Hartree Fock method, which I will explain in detail in the last section.

Hartree Fock wave function and the Slater determinants

Now that we got to know the Hamiltonian in equation 1, we must specify the form of the wave function for many-electron systems. First, the wave function must be separable to satisfy equation 4. Hartree approximately considered the electrons uncorrelated (independent from each other) to build a separable wave function. The square of the wave-function is the probability of finding electrons in a specific volume of space, and the probability of occurring two independent events at the same time is equal to the product of their individual probabilities. Thus, the electronic wave function of N uncorrelated electrons must be equal to the product of the one-electron wave-functions.

This equation is called the Hartree Product. The χ(x)s are one-electron wave functions referred to as spin-orbitals, and each of them is a function of three spatial coordinates and one quantum property called spin coordinate. However, the Hartree product has a severe flow as an electronic wave function. That is, it is not consistent with the indistinguishability of electrons. Note that if we interchange two electrons in the Hartree product, the result term is different.

Moreover, according to the Pauli exclusion principle, an electronic wave function must be antisymmetric, which means that with interchanging the space and spin coordinates of any two electrons, the sign of wave function alters.

To satisfy these requirements, we can use certain linear combinations of Hartree products—note that if a wave function is acceptable, its linear combinations are also acceptable. Consider a two-electron wave function. If the electron one and the electron two occupy χi and χj spin-orbitals, respectively, we have.

Also, we can make another Hartree product by putting electron one in χj and electron two in χi.

None of these Hartree products is antisymmetric, nor are their electrons indistinguishable, but we can make an antisymmetric wave function by combining them linearly.

Likewise, every N-electron wave function can be written as an N-by-N determinant called the Slatter determinant.

Note that each row belongs to an electron in the Slater determinant, and each column represents a spin-orbital. The Hartree product is an entirely uncorrelated wave function, but the anti-symmetrised Slater determinant introduces some correlation between electrons. Namely, the electrons with parallel spin can not be in the same spatial orbitals since, in that case, two rows of Slater determinant become equal—remember that if two rows of a determinant are identical, then the determinant is zero. Therefore, the Hartree Fock method considers a type of correlation, which is called exchange-correlation. However, because the Hartree Fock method does not account for correlation between electrons with opposite spins, it usually is referred to as an uncorrelated method.

The Slater determinant can be built by different combinations. Therefore, we can make multiple Slater determinants. Considering the two-electron wave function case, we have two spatial orbitals ψ1 and ψ2 and four spin orbitals constructed from them, ψ1α, ψ1β, ψ2α, and ψ2β. But in this case, to build a Slater determinant, we only need two spin orbitals, and there are six different possible combinations to make a two-electron Slater determinant out of four spin-orbitals when all permutations are taken into account.

Generally, having N electrons and M spin-orbitals, we can construct ![]() different Slater determinants. However, the Hartree-Fock approach only uses one of them called the Hartree-Fock ground state determinant. The other determinants can represent the excited states of the electronic system. Also, a linear combination of these determinants is a more accurate wave function, which more precisely considers the correlation between electrons. A more elaborate and computationally cumbersome method, configuration interaction (CI), utilises the linear combination of these determinants to describe electronic systems. Using a single Slater determinant arguably equals treating electron-electron repulsion in an average way, which is the essence of the Hartree-Fock approximation.

different Slater determinants. However, the Hartree-Fock approach only uses one of them called the Hartree-Fock ground state determinant. The other determinants can represent the excited states of the electronic system. Also, a linear combination of these determinants is a more accurate wave function, which more precisely considers the correlation between electrons. A more elaborate and computationally cumbersome method, configuration interaction (CI), utilises the linear combination of these determinants to describe electronic systems. Using a single Slater determinant arguably equals treating electron-electron repulsion in an average way, which is the essence of the Hartree-Fock approximation.

Basis sets and the Roothaan equations

Now that we know that the electronic wave function can be built from the linear combination of spin-orbitals, the critical question is how to find spin-orbitals. Each spin-orbital comprises two parts, the spatial function and the spin function. The spatial function is a function of three electron spatial coordinates, and the spin function is related to electron spin, which is a quantum attribute.

Since the Hamiltonian Operator (equation 8) does not affect the spin function, we can consider the spin function as a constant coefficient.

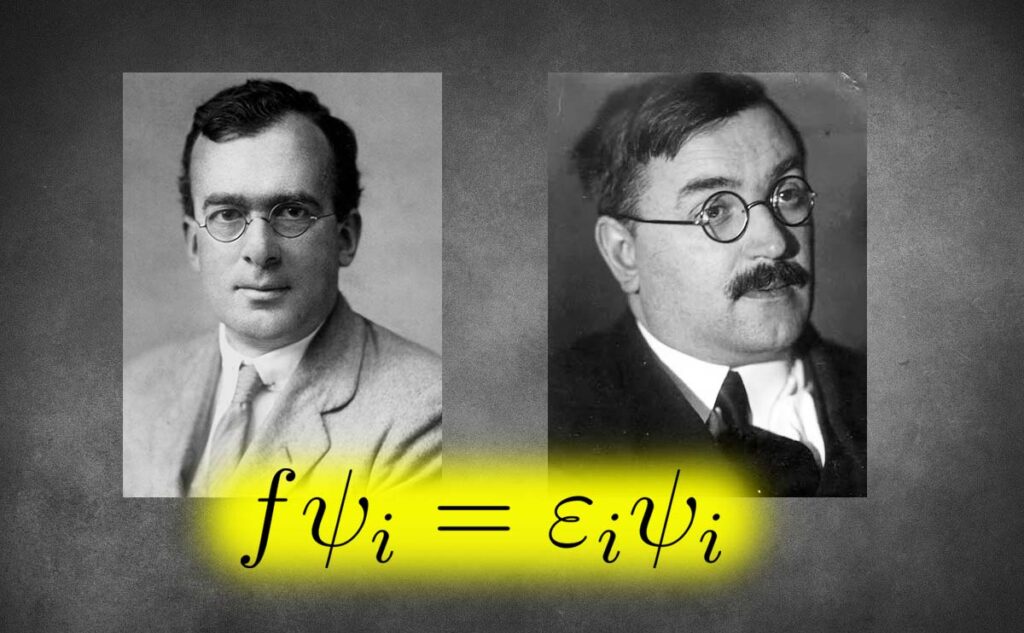

Therefore to solve the problem, we only need to determine the spatial part of spin-orbitals. Clemens C. J. Roothaan and George G. Hall, both graduate students at the time, independently showed that the spatial component could be regarded as a set of known spatial basis functions, referred to as the basis set.

C and φ represent expansion coefficients and known functions in this equation, respectively. The importance of the Roothan-Hall equation is that it reduces the problem of finding the Hartree Fock molecular orbitals to the problem of calculating a set of expansion coefficients, which can be represented by a coefficient matrix. Therefore, we can write the Hartree Fock equation (equation 9) as a solvable matrix equation that can be processed by computer software.

In terms of accuracy, if we could use any complete basis set, which has an infinite set of K and spans the entire phase-space, the expansion would be exact regardless of the form of the basis functions. But, a finite basis set is only exact in the space spanned by its functions, so it is crucial which basis functions compose the basis set; however, as a rule of thumb, the greater the K and larger the basis set, the more precise are the molecular orbitals. But, using a huge basis set is not a practical option in real-world computational problems because the cost of electronic structure computations increases rapidly with the size of the basis set. Therefore, we always have to compromise the basis set size.

The Hartree Fock equation

This section will study the Hartree Fock equation and its components, although I will not provide a detailed derivation because it is meant to be an easy explanation. A keen reader can find a thorough explanation in this reference..

One and two-electron integrals

As I said before, the Hartree-Fock method aims to solve the electronic Schrodinger equation (equation 4) for many-body electronic systems.

This is an eigenvalue equation, and by solving the equation, I mean finding Ψelec vectors and Eelec values that fit the equation. Unfortunately, we can not solve this equation exactly for many-body electronic systems. However, we can find approximate solutions for it using the variation theorem. The variational principle states that any approximate wave function has an energy value above or equal to the exact energy. In other words, if we minimize the electronic energy regarding the spin-orbitals, we can find the closest wave function to the exact one in the restriction of Hartree-Fock theory, which is called the Hartree-Fock ground state wave function.

To apply the variation theorem, Let’s first rearrange equation 4 for energy.

We can substitute Helec with equation 3 and Selec with a single Slater determinant to find the energy equation in terms of Hartree-Fock approximation.

In this equation, I used a linear short-hand notation for the Slater determinant for the sake of conciseness. The electronic Hamiltonian comprises two types of operators. The first two terms are one-electron operators. These operators depend only on the position or momentum of one electron and do not consider the interaction with other electrons. As a two-electron operator, the last term is the sum of repulsion between all electron-pairs and thus involves the position of two electrons simultaneously.

Let us indicate the one-electron operators with hone for simplicity.

We can consider equation 25 as a matrix equation. There are rules for evaluating such equations depending on the type of operators. Using these rules, you can find the expression of energy as

Applying the variation theorem

Now that we have an expression for electronic energy, we can use the variation theorem to solve the electronic Schrodinger equation. According to the variation theorem, the exact wave function always has a lower energy value than any approximate wave function, so the most accurate Hartree Fock wave function is at the minimum regarding changing spin-orbitals (the basis set coefficients). We call the energy of this wave function the Hartree-Fock ground state energy (E0). As a result, δE0 is zero, and we can write the following equation.

In this Equation, CC represents the complex conjugate of the left-hand side terms produced by the differentiation process.

If all the basis-set coefficients were independent, we could use the above equation to minimise the energy directly; however, because spin-orbitals are normal, some basis-set coefficients are dependent. The normalisation requirement of spin-orbitals implies that.

And concerning equation 19 and equation 20 we can write:

And because spin and spatial functions also are orthogonal, this equation can be reduced to

The above equation shows that in each spin-orbitals, one of the basis set coefficients (Cvi) depends on other coefficients, and therefore the E0 is a constraint function of the Cvis. In mathematics, the standard method for finding the local minima of constraint functions is Lagrange’s method of undetermined multipliers. In this method, we introduce a new variable called Lagrange’s multiplier and define a new function (L) related to the multiplier and all other variables; then, we minimize L for all variables. Now let’s use the Lagrange method to find δE0.

Note that we built the Lagrange function simply by adding a zero to the energy expression because the spin-orbitals are normalised.

So the minimum of L and E occurs at the same spot where δL is equal to zero

The second term in this equation can be written as

Where CC indicates the complex conjugate of the left-hand side terms. Using this equation and equation 27 we can write δL as

This equation can be factored to

We can neglect the complex conjugate part because if A+A*=0, then A=0.

Therefore,

Coulomb and exchange operators

Now let’s define coulomb (J) and exchange (K ) operators as

The coulomb operator has a straightforward interpretation. The exact Coulomb interaction between two electrons in the atomic unit is r12-1. Likewise, in the Hartree-Fock approximation, electron one in χa experiences a one-electron potential from χb equal to ![]() and because in equation 38, the summation is over all spin-orbitals, each electron feels Coulomb repulsion from all other electrons. Note that each integral in the summation is independent of the others, which is why the Hartree Fock approximation does not account for the Coulomb correlation between electrons.

and because in equation 38, the summation is over all spin-orbitals, each electron feels Coulomb repulsion from all other electrons. Note that each integral in the summation is independent of the others, which is why the Hartree Fock approximation does not account for the Coulomb correlation between electrons.

On the other hand, the exchange operator has no perceivable classical interpretation and results from exchange-correlation between electrons with parallel spins, which I previously explained. The existence of the exchange operator in the Hartree Fock equation implies that the Hartree Fock method is not entirely uncorrelated and considers the correlation between electrons with parallel spins. Using the Coulomb and exchange operators, we can shorten equation 38 as:

The inside brackets term is the definition of Fock operator f(x). Therefore

This is the Hartree-Fock equation. Note that we separated an unsolvable many-electron problem (equation 4) into N solvable—although approximately—one-electron problems. The appearance of summation in the right-hand side of the equation is because the Slater determinant is formed from a set of spin-orbitals, which provide a certain degree of flexibility; namely, there can be different spin-orbit combinations without changing the expectation value (E0). However, because ε is a Hermitian matrix, we can always find a unitary matrix that transforms ε into a diagonal matrix. The unique set of spin-orbitals corresponding to this specific diagonal ε matrix is called the set of canonical spin-orbitals. It is typical to write equation 42 in its canonical (standard) form, the same as equation 9.

The Self-Consistent field method; How computers solve the Hartree Fock equation

Now that we are familiar with the Hartree Fock equation and how to build a proper wave function for it, In this final section, I can explain how computers solve the Hartree Fock equation for many-body electronic systems. The specific procedure for solving the Hartree Fock equation is called the self-consistent-field (SCF) method. SCF is another name for the Hartree Fock method, and the two terms are used interchangeably in computational literature. Let’s look at the Hartree Fock equation in its canonical form once again.

χ represents a spin-orbital consisting of a spatial and a spin function in this equation. The spin function has only two values (α and β), and its value can be determined according to Pauli’s exclusion principle before self-consistent Field calculation. In the Hartree Fock approach, there are three formalisms to deal with spin function: restricted closed-shell, unrestricted open-shell and restricted open-shell. We can apply one of them according to the multiplicity of the electronic system and eliminate the spin function from equation 9.

Thanks to Roothaan contribution to the SCF approach, we can consider the spatial function a set of known basis functions.

By substituting the basis-set into equation 43, we can write the Hartree Fock equation as

This is an integro-differential equation; however, multiplying by Φ* on the left and integrating it, we can turn it into a matrix equation that is far more computer-friendly.

If you can not see these terms as a matrix equation, consider μ and v as matrix indices with values ranging from 1 to K.

Now let’s define two new matrices.

- The overlap matrix S with elements according to

The overlap matrix quantifies overlap between basis functions that are not orthogonal to each other in general. The diagonal elements of S are unity, and the off-diagonal elements have values ranging from one to zero. The sign of the off-diagonal elements depends on the relative sign of the two basis functions and their relative orientation. The more an off-diagonal element (S) approaches unity, the more its two basis functions overlap.

2. The Fock matrix F with elements according to

The Fock matrix (F) is the matrix representation of the Fock operator (f) —a one-electron operator as I defined in the previous section— with the set of basis functions {Φ}. Because the summation indices (𝜇 and v) in equation 44 range from 1 to K, both the overlapped and Fock matrices are K×K square matrices. They are also Hermitian, which means we can orthogonalize them by a unitary matrix.

With these definitions, now we can write the equation 46 as

Or more compactly as

In this equation, referred to as the Roothann equation, C is a K×K square matrix containing expansion coefficients of the basis functions (equation 44), and ε is a diagonal matrix of the orbital energies.

Solving the Roothaan equation—or equivalently the Hartree-Fock equation—from the perspective of computational software means finding a proper coefficient matrix (C) that minimises the system’s total energy. The Roothaan equation (equation 50) is not a standard eigenvalue problem due to the non-orthogonality of the basis functions, which gives rise to the overlap matrix. Therefore, we need to consider a procedure to orthogonalise the basis functions. If we somehow manage to orthogonalise the basis functions, the overlap matrix becomes the unit matrix, and Roothaan’s equations turn into a set of standard eigenvalue problems.

If we have a set of non-orthogonal basis functions {Φ}, it is always possible to find a transformation matrix (X) that transforms the non-orthogonal set to an orthogonal one.

and

We can convert the overlap matrix to a unit matrix using this transformation matrix.

There are two methods for finding the transformation matrix—symmetric orthogonalization and canonical orthogonalization—which I will not explain in this article. Nevertheless, having the X, we can orthogonalise the basis functions and eliminate the overlap matrix (S) from Roothaan’s equations. Afterwards, we can solve the equation directly by diagonalizing the Fock matrix. However, we have to transform all the two-electron integrals, which is very time-consuming. The SCF (Hartree Fock) method uses a more efficient way to deal with the problem. Consider a new coefficient matrix (C’) related to the matrix by X

Where X-1 is the inverse of the transformation matrix. Substituting C from the above equation into the Rootaan equations (equation 50) gives

Multiplying both sides of this equation by the adjoint of the transformation matrix (X✝) gives

If we define a transformed Fock matrix (F’) such that

We can define transformed Roothaan equations as

The SCF style of solving Roothan equations is finding the transformation matrix, transforming the Fock matrix and solving the transformed Roothaan equations. Finally, the coefficient matrix is calculated from equation 57. Indeed, the self-consistent field instruction is more elaborate than this. The Roothaan equations are nonlinear and need to be solved by an iterative approach because the Fock matrix depends on the expansion coefficients. Before explaining the self-consistent field procedure, we need to know the density matrix concept and the Fock matrix’s explicit form.

The density matrix

Let us expand the molecular orbitals as a set of basis functions from equation 44

From this equation, we can define the density matrix as

The Density matrix is directly related to the expansion coefficients, and it can represent the Hartree-Fock wave function completely. The density matrix is important because, in the Self-consistent field instruction, the Fock operator is written in terms of the density matrix (you will see it in the following subsection), and it solves the Hartree Fock equation iteratively concerning the charge density. The Hartree Fock codes first guess a charge density describing the position of the system’s electrons. Then they use this conjectural charge density to estimate an initial Fock operator. Using this operator, they solve one-electron Schrodinger-like equations (equation 43) to find the molecular orbitals {ψi}. Then they can build a better charge density from these recent molecular orbitals and guess a more accurate Fock operator. The self-consistent field algorithm repeats this procedure until the Fock operator no longer changes. In other words, the SCF procedure continues the loop of making the Fock operator and charge density from each other until the field (the two-electron part of the Fock operator) that produces a specific charge density becomes identical (consistent) with the field which would be calculated from that charge density. Therefore we also call the Hartree Fock method the self-consistent-field method. In the following subsection, we scrutinize the Fock operator to find an explicit expression for it which we will use in the last part to demonstrate how the Hartree Fock method works.

The Fock matrix

Let us have another look at equation 41. In this equation, the Fock operator is

However, if we consider the simplest form of the Hartree Fock equation, the restricted closed-shell Hartree Fock equation, the Fock operator slightly differs from the above equation (for proof, see section 3.4.1 of reference 1).

However, if we consider the simplest form of the Hartree Fock equation, the restricted closed-shell Hartree Fock equation, the Fock operator slightly differs from the above equation (for proof, see section 3.4.1 of reference 1).

And

Now we can write the Fock operator as

And then incorporate the basis functions (equation 44) into it.

We can pull expansion coefficients out of the integral and define them as a density matrix (equation 64).

Finally, using the definition of the Fock matrix (equation 48) we can write

The first integral term, called core-Hamiltonian (Hcore), involves only one-electron operator (hone see the above passage) and is over the coordinates of one electron (r1) each time. The core-Hamiltonian represents an electron’s kinetic energy and nuclear attraction, neglecting the repulsion with other electrons. Unlike the full Fock matrix, the core-Hamiltonian matrix needs to be assessed only once as the beginning of the Self-consistent field procedure. The remaining part of the Fock matrix is a two-electron part, denoted by G, which consists of the density matrix and the two-electron integrals.

At this point, we have enough materials to properly describe the Self-consistent field procedure, which is the topic of the final part.

The self-consistent field algorithm

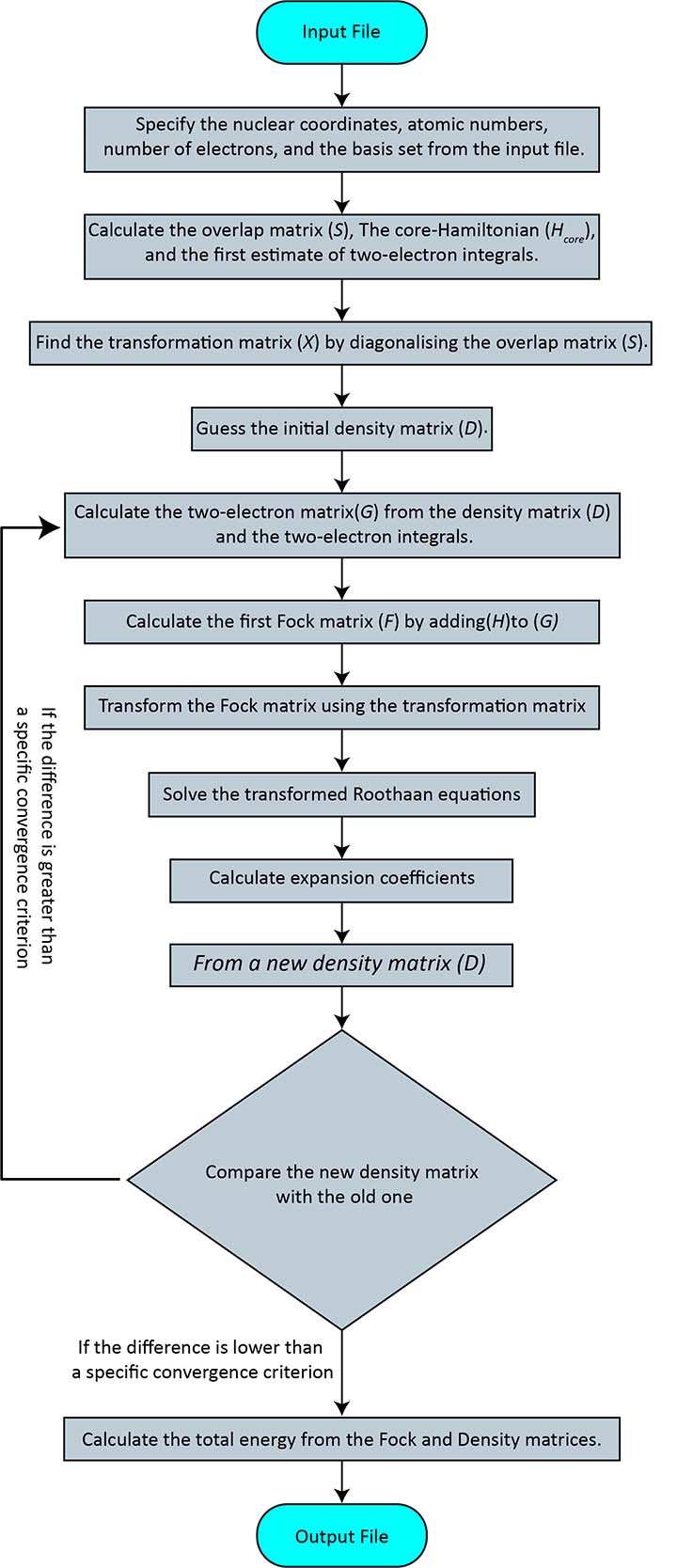

- Specify the nuclear coordinates, atomic numbers, number of electrons, and the basis set from the input file.

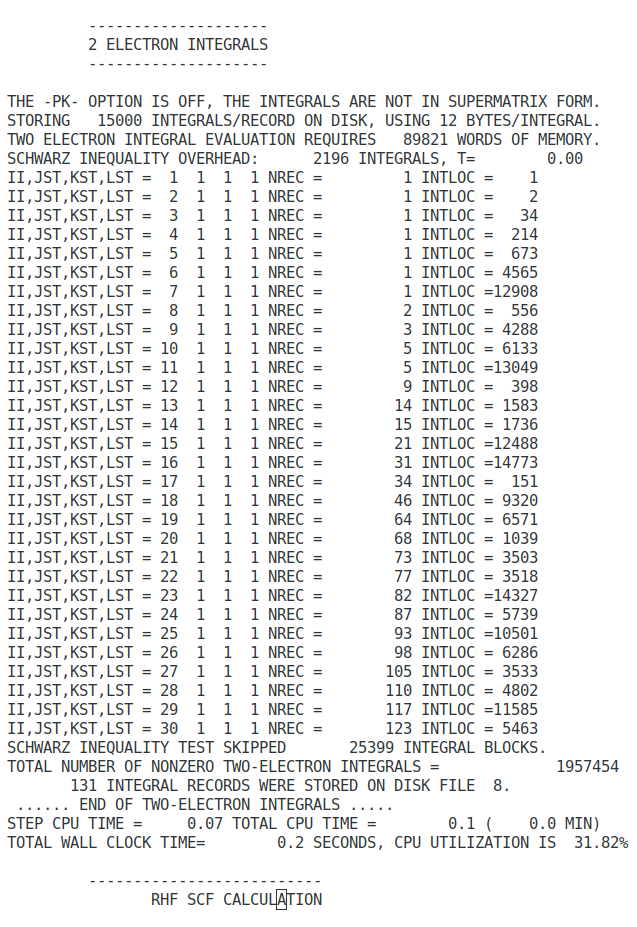

- Calculate the overlap matrix (S), The core-Hamiltonian (Hcore), and the first estimate of two-electron integrals.

- Find the transformation matrix (X) by diagonalising the overlap matrix (S).

- Guess the initial density matrix (D).

- Calculate the two-electron matrix G (equation 76 and 77) from the density matrix (D) and the two-electron integrals.

- Calculate the first Fock matrix (F) by adding H to G (equation 77).

- Transform the Fock matrix using the transformation matrix, F′=X✝FX.

- Solve the transformed Roothaan equations, F′C′=C′𝜺.

- Calculate expansion coefficients, C=XC′.

- From a new density matrix (D) using C and equation 64.

- Compare the new density matrix with the old one and check how different they are. If the difference is greater than a specific convergence criterion, return to step 5. If the difference is smaller than the criterion, go to the final step.

- Calculate the total energy from the Fock and Density matrices.

Follow me on LinkedIn

References

Szabo, A., & Ostlund, N. S. (1989). Modern quantum chemistry: Introduction to advanced electronic structure theory. McGraw-Hill.

Jensen, F. (2017). Introduction to Computational Chemistry, 3rd Edition. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Foresman, J. B. (2016). Exploring chemistry with electronic structure methods. Place of publication not identified: Gaussian.

Congratulation!

As far as I can tell, this is the simplest text for learning one of the most difficult concepts in computational chemistry.

Excellent explanation about the Hartree Fock method; thank you for shear.

Excellent!!!

Could you give a similar explanation for DFT ?

Thank you Zhang. Acctually I’m working on it.

Looks neat, but the equations and figures are not showing currently (tested firefox, chrome and mobile). Hopefully the fix is easy, I’m looking forward to reading this to help me with my computational physics course.

Thank you for informing us.

Would you please tell us from where you checked our website?

Is the equation not loading even in incognito mode?

Excellent explanations. So simply written and understandable. Keep doing this please

Keep up the good work!!! Wonderful

This is so helpful! I am doing a seminar on this and this is wonderful help!! This is the best explanation I have ever seen! Thank you.

This is truly one of the most complete ad easy to digest explanation on the HF method. Thank you, very helpful. If you could do the same for post HF methods like CASSCF it would be golden.

Excellent! Thank you.

This is brilliant; thank you!